A Unified Target–Operator–Diagnostics Framework for LLM Post-Training (Part I, Theoretical Framework)

Introducing TOD (Target–Operator–Diagnostics), a unified framework for LLM post-training.

From Recipes to Regimes: A Target–Operator–Diagnostics Framework for LLM Post-Training

Authors: Shaobo Wang*, Junxin Fan*, Xingzhang Ren, Dayiheng Liu†, Linfeng Zhang†

Affiliations: Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Alibaba Qwen Team, Fudan University

*Equal contribution †Corresponding authors

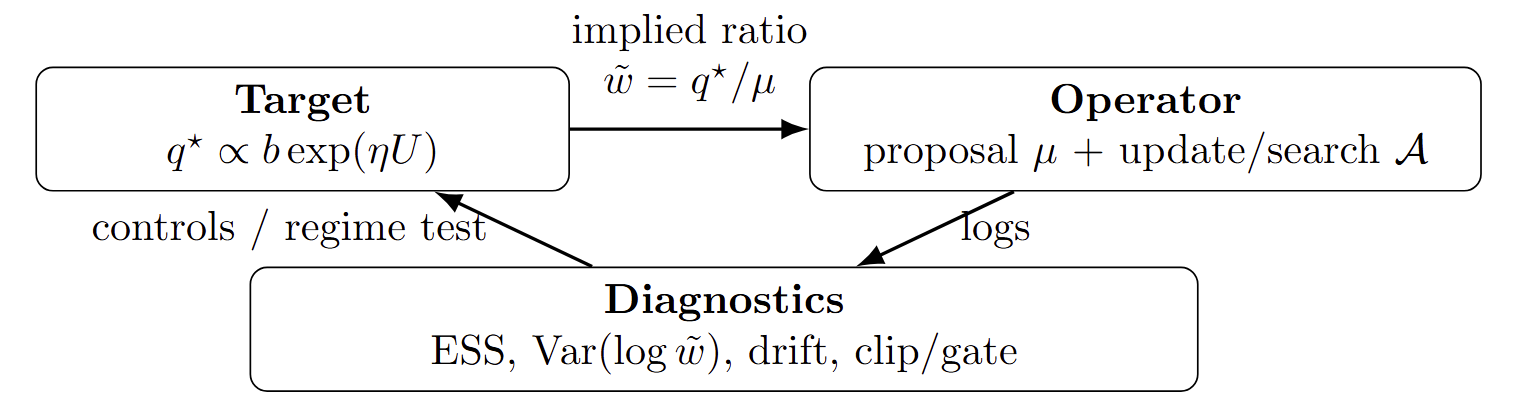

Post-training is often framed as a multiple-choice question among methods like SFT, DPO, or PPO, yet in real systems, implementation details—such as on-policy versus off-policy sampling, candidate sources, and mechanisms like clip or gate—typically exert a stronger influence on performance and stability than the method’s label. To unify and compare post-training recipes, we propose the TOD (Target–Operator–Diagnostics) framework: the Target defines the desired behavior; the Operator specifies how candidates are generated and acted upon (via parameter updates during training or reranking/search at inference); and Diagnostics provide quantifiable metrics to measure alignment between the target and the current sampling distribution, revealing the system’s operational regime. Our core finding is that when the effective sample size is sufficiently high, the system enters a swap-stable regime where different operators are nearly interchangeable under matched compute; but when effective sample size is low, it falls into an operator-dominated regime, where fine-grained choices—such as clip versus gate or token-level versus sequence-level feedback—dictate outcomes and often trigger failure modes.

Part I presents the TOD framework and its theoretical regime picture. Part II (future work) will provide empirical validation of the diagnostics and regime predictions.

Overview

Large language models are almost always adapted after pre-training using separate “methods” like SFT, DPO, or PPO. In practice, small implementation details often matter more than the choice of method.

These procedures are usually introduced as separate “methods.” In practice, we repeatedly observe the following pattern. Different methods are configured with what is intended to be the same behavioral goal-similar reward or preference signals, similar anchors, similar constraints-but small changes in the update rule, proposal distribution, or implementation details can lead to very different behavior [8,7]. In some configurations, changing from a preference surrogate to proximal RL, or from amortized training to test-time search, barely changes downstream metrics. In others, the same swap leads to instability, drift from the reference policy, or collapse in diversity [17,12,18].

This suggests that the central difficulty is not only “which method is better”, but that we lack a precise way to say when two recipes are effectively aiming at the same target and when differences in the operator are expected to dominate. At scale, this shows up as a large number of failed runs and hyperparameter sweeps whose outcomes are hard to predict or interpret [7,8].

This work addresses that problem in two steps. First, we introduce a simple framework that separates three components of a post-training or inference-control procedure:

- A target distribution \(q^*(y \mid c)\) describing the intended behavior.

- An operator \((\mu,\mathcal{A})\) describing how we sample candidates and act on them.

- Diagnostics \(\mathcal{D}\) that summarise how the operator is coupled to the target in the regimes we care about.

Within this framework, many familiar methods-supervised fine-tuning, preference optimization, KL-regularised RL, on-policy distillation, and test-time search-can be written as different operators applied to closely related targets [14,16,17,2,3,13].

Second, we show that these components interact through a single ratio

\[\tilde w(y,c) = \frac{q^*(y \mid c)}{\mu(y \mid c)}\]and that simple diagnostics derived from this ratio are enough to distinguish regimes where operators are effectively interchangeable from regimes where they are not. When the proposal \(\mu\) has good overlap with \(q^*\) and the induced importance weights have moderate tails, different operators that share the same target tend to produce similar outcomes under matched compute. When overlap deteriorates or the target becomes very sharp, the induced weights become heavy-tailed, and details of the operator-on- versus off-policy sampling, token- versus sequence-level objectives, clipping versus gating-have a large and systematic effect [11,17,12,18,5,10].

We refer to this decomposition as the Target–Operator–Diagnostics (TOD) framework. It has two main uses. Conceptually, it gives a common language for describing and comparing post-training recipes in terms of their targets and operators, rather than their historical names. Practically, it yields concrete diagnostics that can be logged in real systems to identify feasible regimes, to explain when “operator swaps” are safe, and to guide the design of adaptive controllers that keep training in stable regions.

The rest of this post adopts this framework. We first define the target class we consider and summarise common post-training objectives as instances of it. We then describe operator families—how different methods choose their proposal distribution and update or selection rule. Finally, we show how diagnostics based on the ratio \(\tilde w\) delineate swap-stable and operator-dominated regimes, and briefly describe an adaptive controller that keeps training in the former.

1. Basic Definitions

We write \(c\) for a context (prompt, dialogue state, task input) and \(y\) for an output sequence.

A post-training or inference-control procedure is described by a triple

\[\small \big(q^*,\,(\mu,\mathcal{A}),\,\mathcal{D}\big)\]where each component is defined as follows.

Target: \(q^*(\cdot \mid c)\) is the intended distribution over outputs for each context. In this work we focus on targets that can be written as an anchored exponential tilt,

\[\small q^*(y \mid c) \propto b(y \mid c)\,\exp\big(\eta\,U(y,c)\big).\]Here \(b(y \mid c)\) is an anchor or base distribution, such as a pretrained model, a reference policy, a previous policy, or a mixture of these. The function \(U(y,c)\) is a utility, such as supervised log-likelihood, a preference score, a scalar reward from a verifier, or a teacher score. The scalar \(\eta \in \mathbb{R}\) controls the sharpness of the tilt; equivalently one can write a temperature \(T = 1/\eta\). Different choices of \(b\), \(U\), and \(\eta\) recover familiar post-training objectives. In Section 2 we summarise the target families we consider in a catalog table to fix notation and assumptions.

Operator: The pair \((\mu,\mathcal{A})\). The distribution \(\mu(\cdot \mid c)\) is the proposal that actually generates candidate outputs. It may coincide with a supervised dataset policy, with a previous policy \(\pi_{\text{old}}\), with the current policy \(\pi_\theta\) , or with a mixture or replay distribution. The mapping \(\mathcal{A}\) describes the action taken using these candidates. In training, \(\mathcal{A}\) corresponds to an update rule that changes parameters (amortisation). At inference time, \(\mathcal{A}\) may resample, rerank, or select candidates without changing parameters. Many practical systems use hybrids that combine both [7,8].

Diagnostics: \(\mathcal{D}\) are loggable statistics computed from samples, utilities, and anchors. In our experiments the primary diagnostic is an estimate of effective sample size (ESS) associated with the target-proposal pair. We also track tail behaviour of importance weights, activation of clipping or gating mechanisms, and drift from anchor distributions. These quantities are used to identify different regimes and to decide when changing the operator is likely to preserve behaviour [11,17,12,18].

1.1 The ratio that couples target and operator

The interaction between the target \(q^*\) and the proposal \(\mu\) is governed by the ratio

\[\small \tilde w(y,c) = \frac{q^*(y \mid c)}{\mu(y \mid c)}.\]This ratio is rarely computed explicitly in large-scale systems, but it determines how informative samples from \(\mu\) are for the target \(q^*\) . When \(\mu\) has good overlap with \(q^*\) and the tails of \(\tilde w\) are moderate, many reasonable choices of update or selection rule \(\mathcal{A}\) behave similarly under matched compute. When \(\mu\) has poor overlap or the target is very sharp, \(\tilde w\) becomes heavy-tailed, a small number of samples dominate, and details of \(\mathcal{A}\) (for example token- versus sequence-level objectives, clipping versus gating, and on- versus off-policy proposals) have a large effect.

In later sections we make this connection quantitative. Effective sample size and tail statistics serve as practical diagnostics for the ratio landscape \(\tilde w\) , and allow us to delineate regimes in which different operators are effectively interchangeable and regimes in which they are not.

2. Target Design

We keep the same notation as above. For each context \(c\) , \(y\) denotes an output sequence. We write \(b(y \mid c)\) for a base or anchor distribution and \(U(y,c)\) for a scalar utility.

2.1 Canonical Target

The target class we use throughout is the anchored exponential tilt

\[\small q^*(y \mid c) \propto b(y \mid c)\,\exp\big(\eta\,U(y,c)\big),\]with sharpness \(\eta > 0\) .

As \(\eta \to 0\) , the target approaches the base \(b\) . As \(\eta \to \infty\) , it concentrates on \(\arg\max_y U(y,c)\) inside the support of \(b\) . This form is the optimizer of a KL‑regularised design problem:

\[\small q^*(\cdot \mid c) \in \arg\max_{q(\cdot\mid c)} \Big\{\mathbb{E}_{y\sim q}[U(y,c)] - \tfrac{1}{\eta}\,\mathrm{KL}\big(q(\cdot\mid c)\,\Vert\,b(\cdot\mid c)\big)\Big\}.\]Thus \(b\) encodes how conservative we want to be relative to a reference, and \(\eta\) controls how strongly we tilt toward higher utility.

With multiple signals \(U_k\) (for example helpfulness, safety, style), we write

\[\small q^*(y \mid c) \propto b(y \mid c)\, \exp\Big(\sum_k \eta_k\,U_k(y,c)\Big),\]with separate sharpness parameters \(\eta_k\) . Hard constraints can be implemented by restricting the support of \(b\) .

The rest of the paper works entirely within this family. Different “targets” are different choices of base \(b\) , utilities \(U_k\) , and sharpness vector \(\{\eta_k\}\) .

2.2 Target Catalog

Table 1 organises common target designs in this exponential‑tilt form. Each row specifies the base \(b\) , the utility \(U\) , how the utility is constructed, and where the target appears in practice. The associated operators (SFT, DPO, PPO/GRPO, OPD, test‑time search) will be discussed later; here we only fix the design lens.

| Target family | Anchor / base \(b(y \mid c)\) | Utility \(U(y,c)\) | Sharpness parameters | Typical construction and usage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scalar reward tilt (RL / RLVR) | Reference policy \(\pi_{\mathrm{ref}}(y \mid c)\) | Scalar reward \(r(y,c)\) from a reward model or verifiable task | Single \(\eta > 0\) | Canonical RLHF / RLVR target: tilt a reference model toward higher reward while keeping proximity via \(b\) . |

| Preference‑induced tilt | Reference policy \(\pi_{\mathrm{ref}}(y \mid c)\) | Latent score \(r(y,c)\) consistent with pairwise preferences | Scale \(\eta\) matched to preference noise | Bradley-Terry / logistic choice model implies \(q^* \propto \pi_{\mathrm{ref}}\exp(\eta r)\) ; DPO‑style objectives target this distribution [16]. |

| Multi‑objective reward / constraints | Anchor as above, often a mixture of \(\pi_{\mathrm{old}}\) and \(\pi_{\mathrm{ref}}\) | Sum \(\sum_k \eta_k U_k(y,c)\) over components such as helpfulness, safety, style | Vector \(\{\eta_k\}\) | Used when combining several reward or verifier signals; safety or style often enter as additional \(U_k\) or support restrictions. |

| Two‑anchor proximal target | Geometric mixture \(b_{\tau,\beta}(y \mid c) \propto \pi_{\mathrm{old}}^{\tau/(\tau+\beta)} \pi_{\mathrm{ref}}^{\beta/(\tau+\beta)}\) | Scalar reward \(r(y,c)\) | Effective sharpness \(\eta = 1/(\tau+\beta)\) | Design target for proximal on‑policy RL with two KL anchors; the operator enforces trust regions around \(\pi_{\mathrm{old}}\) and \(\pi_{\mathrm{ref}}\) . |

| Verifier / rejection‑based tilt | Anchor \(b(y \mid c)\) given by a base generator (pretrained model, old policy, or mixture) | Utility from verifier outputs, e.g. pass/fail or partial‑credit scores | \(\eta\) set by desired selectivity | RLVR‑style designs where a verifier supplies a scalar signal; rejection / resampling operators approximate this target. |

| Teacher / distillation tilt | Student‑anchor \(\pi_{\mathrm{old}}(y \mid c)\) or teacher \(\pi_{\mathrm{teach}}(y \mid c)\) | Utility proportional to log teacher density, e.g. \(U(y,c) = \log \pi_{\mathrm{teach}}(y \mid c)\) or a margin score | \(\eta\) encodes how sharply we trust the teacher | On‑policy distillation (OPD) and KD variants: define a moving target proportional to teacher scores on student rollouts. |

| Finite‑candidate posterior | Base \(b(y \mid c)\) restricted to a candidate set \(C(c) = \{y_1,\dots,y_K\}\) | Same scalar utility \(U(y,c)\) as above, evaluated only on candidates | \(\eta\) or \(\{\eta_k\}\) as in the full‑support case | Exact target used when we work with finite candidate sets (e.g. reranking or best‑of‑ \(K\) ), both in training and at test time. |

Table 1. Target catalog in utility‑posterior form. Each entry is of the form

\[\small q^*(y \mid c) \propto b(y \mid c)\,\exp\big(\eta\,U(y,c)\big)\]or its multi‑objective extension. Operator choices (proposal, update rule, trust region, etc.) are discussed in later sections; here they are treated as separate from target design.

2.3 Two anchors as a single base

Many proximal on‑policy RL recipes use two distinct anchors: a previous policy \(\pi_{\mathrm{old}}\) to control update size and an optional frozen reference \(\pi_{\mathrm{ref}}\) to control drift. A clean design objective for a single update is

\[\small \pi^*(\cdot \mid c) \in \arg\max_{\pi(\cdot\mid c)} \Big\{\mathbb{E}_{y\sim \pi}[r(y,c)] - \tau\,\mathrm{KL}(\pi \,\Vert\, \pi_{\mathrm{old}}) - \beta\,\mathrm{KL}(\pi \,\Vert\, \pi_{\mathrm{ref}})\Big\},\]with non‑negative coefficients \(\tau,\beta\) .

This objective has a closed‑form optimizer of the same utility‑posterior form. Define the geometric‑mixture base

\[\small b_{\tau,\beta}(y \mid c) \propto \pi_{\mathrm{old}}(y \mid c)^{\tau/(\tau+\beta)}\,\pi_{\mathrm{ref}}(y \mid c)^{\beta/(\tau+\beta)},\]and the effective sharpness \(\eta = 1/(\tau+\beta)\) . Then the optimizer satisfies

\[\small \pi^*(y \mid c) \propto b_{\tau,\beta}(y \mid c)\,\exp\big(\eta\,r(y,c)\big).\]This observation is purely about target design. It says that “old‑policy proximity” and “reference anchoring” combine into a single effective base \(b_{\tau,\beta}\) , while the reward enters only through \(r\) and the sharpness \(\eta\) . Trust‑region mechanisms implemented in code (ratio clipping, sequence‑level gates, etc.) live in the operator, not in this design equation [17,12,18,5,10].

In what follows, whenever proximal RL or RLVR methods are discussed, we implicitly refer to this two‑anchor target as the design reference. The operator description will specify how a particular algorithm approximates or executes this target under finite samples and compute.

3. Diagnostics Design

Diagnostics are the third component of the TOD description. They are computed from samples, utilities and anchors, and are used to understand how the proposal \(\mu\) is coupled to the target \(q^*\) in practice.

Among the diagnostics we considered, effective sample size (ESS) derived from the ratio

\[\small \tilde w(y,c) = \frac{q^*(y \mid c)}{\mu(y \mid c)}\]is the most informative and the most directly tied to feasibility. This section defines ESS in our setting and explains how we use it to distinguish regimes.

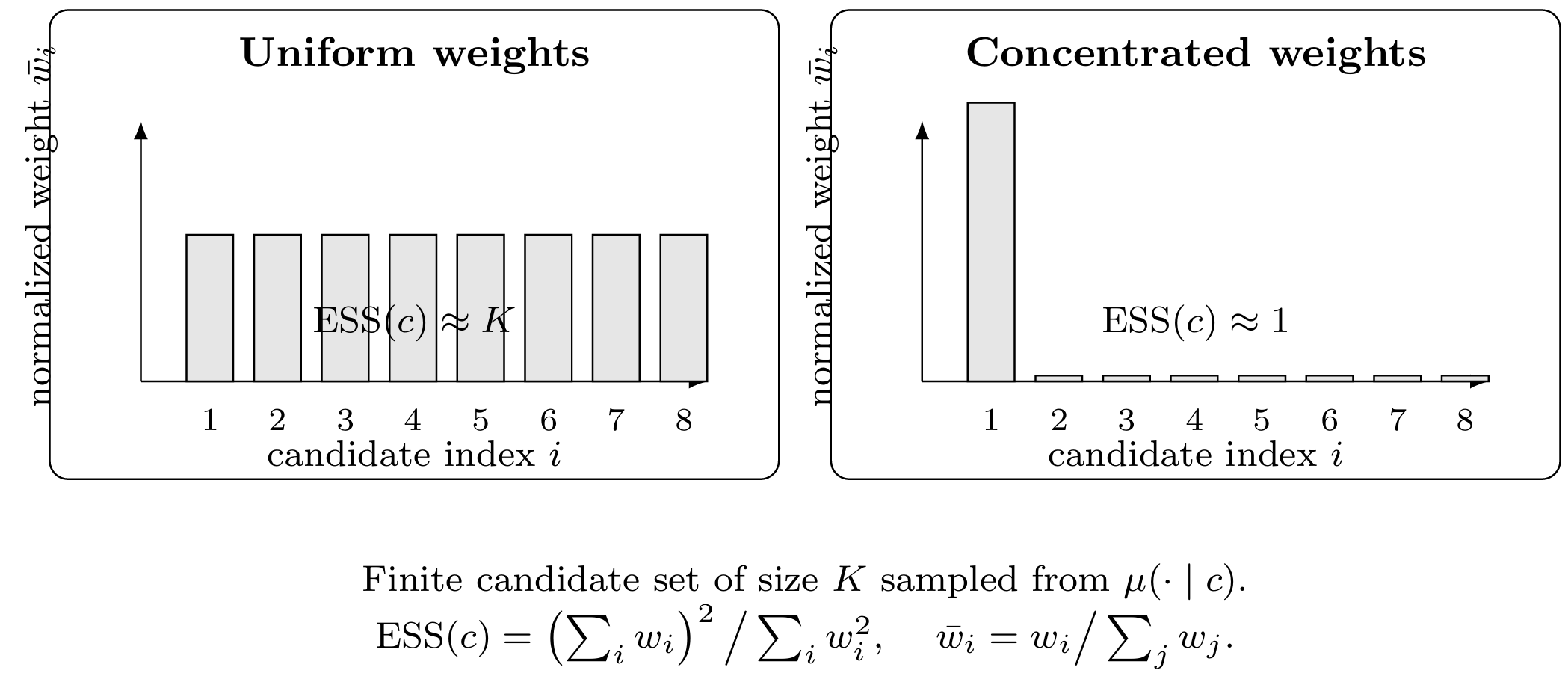

3.1 Context-wise Effective Sample Size

Fix a context \(c\) , and draw \(K\) candidate outputs

\[\small y_1,\dots,y_K \sim \mu(\cdot \mid c).\]For each candidate we can compute an unnormalised importance weight

\[\small w_i \propto \frac{q^*(y_i \mid c)}{\mu(y_i \mid c)}.\]In the utility-posterior form \(q^*(y \mid c) \propto b(y \mid c)\exp(\eta U(y,c))\) , this can be written as

\[\small w_i \propto \frac{b(y_i \mid c)}{\mu(y_i \mid c)} \exp\big(\eta\,U(y_i,c)\big).\]Let \(\bar w_i = w_i / \sum_{j=1}^K w_j\) denote the normalised weights. The (context-wise) effective sample size is defined as

\[\small \mathrm{ESS}(c) = \frac{1}{\sum_{i=1}^K \bar w_i^2} = \frac{\left(\sum_{i=1}^K w_i\right)^2}{\sum_{i=1}^K w_i^2}.\]This quantity always lies between \(1\) and \(K\) . If all weights are equal, \(\bar w_i = 1/K\) for all \(i\) , then \(\mathrm{ESS}(c) = K\) , meaning that all samples contribute equally. If a single weight dominates, \(\bar w_i \approx 1\) for some \(i\) , then \(\mathrm{ESS}(c)\) is close to \(1\) , meaning that, in effect, only one sample is informative for the target.

It is often convenient to work with the relative ESS,

\[\small \mathrm{ESS}_{\mathrm{rel}}(c) = \frac{\mathrm{ESS}(c)}{K},\]which lies in \((0,1]\) and can be compared across different candidate set sizes.

In our experiments, ESS is computed on finite candidate pools (for example, the \(K\) rollouts generated for a context at a given training step, or the candidate set used in test-time search). We then aggregate across contexts by looking at statistics such as the median or the lower quantiles of \(\mathrm{ESS}_{\mathrm{rel}}(c)\) .

3.2 Interpretation as a feasibility diagnostic

ESS provides a single number that summarises how well the proposal \(\mu\) covers the parts of output space that matter under \(q^*\) .

When \(\mathrm{ESS}(c)\) is close to \(K\) for most contexts, the weights are close to uniform and the ratio \(\tilde w\) is effectively flat on the sampled candidates. In this regime, many reasonable operators \(\mathcal{A}\) that use the same candidates and utilities tend to produce similar updates or selections under matched compute. Empirically, swapping between operators (for example, between a preference surrogate and a proximal RL update) while keeping the same target produces minimal changes in behaviour, provided compute is matched.

When \(\mathrm{ESS}(c)\) is small for a substantial fraction of contexts, the weights are highly concentrated and the ratio \(\tilde w\) is effectively heavy-tailed. A small number of candidates dominate the target expectations. In this regime, details of \(\mathcal{A}\) matter: different update rules may respond differently to the same few high-weight samples, and mechanisms such as clipping and gating become active. Empirically, operator swaps in this regime lead to systematic and sometimes large differences in behaviour even when targets and budgets are nominally matched.

We therefore treat ESS as a primary diagnostic for feasibility. High ESS indicates a “well-covered” regime where target expectations can be estimated reliably and operator choices are comparatively robust. Low ESS indicates a fragile regime where the same target is difficult to realise with the available proposal and budget.

3.3 Tail behaviour and auxiliary diagnostics

In addition to ESS, we log several auxiliary quantities that are closely related to the tail behaviour of \(\tilde w\) . Examples include the variance of \(\log w_i\) within a context, the maximum normalised weight \(\max_i \bar w_i\) , and the cumulative weight mass of the top few candidates. These statistics are not used as primary decision variables, but they help interpret situations where ESS is moderate but a small number of very high-weight samples still exist [11].

We also log measures tied to specific operators, such as the frequency with which ratio-based clipping or gating is active and the divergence between the current policy and its anchors. These are discussed in more detail in the section on operators. Conceptually, however, they should be understood as consequences of the same underlying ratio landscape \(\tilde w\) : when tails become heavy, trust-region mechanisms bind more frequently and drift from anchors becomes harder to control.

In the next section we introduce operator families and show how ESS and related diagnostics delineate regimes in which different operators approximate the same target and regimes in which their behaviour diverges.

4. Operator Families

The operator is the pair \((\mu,\mathcal{A})\) . It specifies how we obtain candidates and what we do with them, given a fixed target \(q^*(\cdot \mid c)\) .

The proposal \(\mu(\cdot \mid c)\) is the distribution that actually generates candidate outputs. In practice it may be a supervised dataset distribution, a previous policy \(\pi_{\text{old}}\) , the current policy \(\pi_\theta\) , or a mixture. This is where the usual “on-policy versus off-policy” distinction enters: if \(\mu\) is fixed and independent of the current policy, we are off-policy; if \(\mu\) tracks \(\pi_{\text{old}}\) or \(\pi_\theta\) , we are on-policy; mixtures and replay buffers give hybrid cases.

The action \(\mathcal{A}\) describes how we act on these candidates and their utilities. In amortised training, \(\mathcal{A}\) is an update rule that changes parameters, approximately projecting the current model toward the target. At inference time, \(\mathcal{A}\) may resample, rerank, or select candidates according to their utilities or induced weights without changing parameters. Many practical systems combine both, for example by training a model and then applying test-time reranking on top.

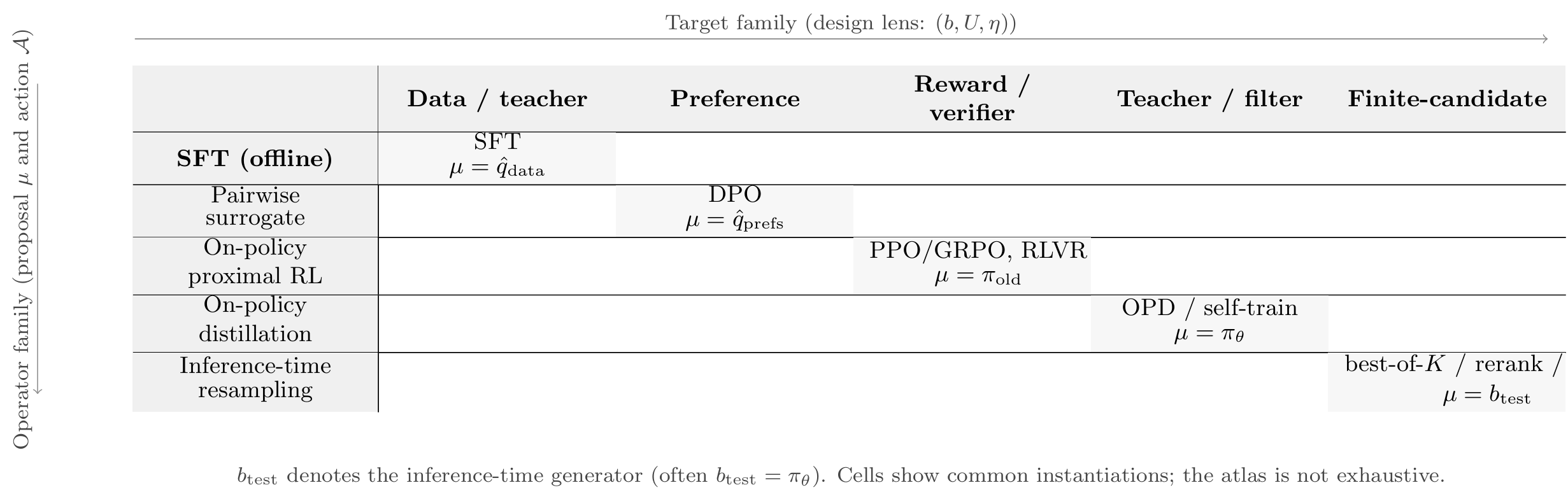

From the TOD perspective, different “methods” correspond to different choices of \(\mu\) and \(\mathcal{A}\) sitting on top of the same or closely related targets [14,16,17,12,18,2,3,13]. Table 2 organises several operator families that are widely used in LLM post-training and inference control.

4.1 Operator Catalog

In this table, the “target lens” column refers back to the target designs in Section 2. We keep the description at the level of distributions and operators, without committing to a particular optimiser or implementation detail.

| Family | Target lens (design) | Proposal \(\mu(y \mid c)\) | Action \(\mathcal{A}\) | On-/off-policy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised fine-tuning (SFT) | Explicit data target or utility posterior with \(U\) from supervised log-likelihood | Empirical data distribution \(\hat q_{\text{data}}(y \mid c)\) | Amortised MLE / forward-KL projection of \(\pi_\theta\) onto \(\hat q_{\text{data}}\) | Off-policy [14] |

| Preference surrogate (DPO-like) | \(pi_{mathrm{ref}}\)-tilted utility posterior \(q^* \propto \pi_{\mathrm{ref}}\exp(\eta r)\) | Preference dataset over pairs \((y^+,y^-)\) | Pairwise logistic surrogate that implicitly fits the Gibbs target induced by latent scores \(r(y,c)\) | Off-policy (typically) [16] |

| Proximal on-policy RL (PPO/GRPO) | Two-anchor utility posterior with reward \(r(y,c)\) and base \(b_{\tau,\beta}\) as in Section 2.3 | Previous policy \(\pi_{\mathrm{old}}(y \mid c)\) (or \(\pi_\theta\) ) | On-policy gradient updates with ratio-based trust region (clipping or gating, token- or sequence-level) | On-policy |

| Verifier-driven RL / RLVR | Verifier or reward-model utility posterior \(q^* \propto \pi_{\mathrm{ref}}\exp(\eta r_{\text{ver}})\) | Rollouts from \(\pi_{\mathrm{old}}\) or \(\pi_\theta\) | On-policy updates using scalar verifier scores (advantages) with KL or ratio constraints to anchors | On-policy |

| On-policy distillation / self-train | Teacher-driven utility posterior with \(U(y,c) = \log \pi_{\mathrm{teach}}(y \mid c)\) or related score | Current student policy \(\pi_\theta(y \mid c)\) | Iterated on-policy projection (reverse-KL / cross-entropy) of \(\pi_\theta\) toward teacher-defined weights | On-policy |

| Test-time reranking / search | Same utility posterior as above, restricted to a finite candidate set \(C(c)\) | Sampling policy at test time (e.g. base decoder, \(\pi_\theta\) ) | Sample–score–resample or select within \(C(c)\) ; no parameter update, only inference-time selection | Inference-only [13,6] |

Table 2. Operator families in TOD form. Each family is described by its target lens, proposal \(\mu\) , and action \(\mathcal{A}\) . The target designs themselves were introduced in Section 2; here we focus on how different methods choose \(\mu\) and \(\mathcal{A}\) on top of those targets.

4.2 Relation to the target and diagnostics

Given a fixed target \(q^*\) , changing the operator means changing \(\mu\) , \(\mathcal{A}\) , or both. In the TOD view, these changes are evaluated through the same coupling ratio

\[\small \tilde w(y,c) = \frac{q^*(y \mid c)}{\mu(y \mid c)},\]and its diagnostics such as ESS.

For example, SFT and a preference-based surrogate may be configured to aim at the same implicit target on a given distribution of contexts, but SFT uses a fixed supervised dataset as \(\mu\) , while the preference surrogate uses a different off-policy dataset. Proximal RL and verifier-driven RLVR use on-policy \(\mu\) and enforce trust regions around anchors, but they differ in how \(\mathcal{A}\) uses scalar rewards or verifier scores. On-policy distillation and test-time search may be based on the same teacher or verifier signals; the former amortises them into \(\pi_\theta\) , while the latter only uses them to select among candidates at test time.

In later sections, when we discuss regimes and operator swaps, we will always refer back to descriptions of this form: fixed target, specified proposal \(\mu\) , specified action \(\mathcal{A}\) , and diagnostics computed from the induced weights \(\tilde w\) . This makes statements about equivalence or divergence precise, rather than being tied to method names.

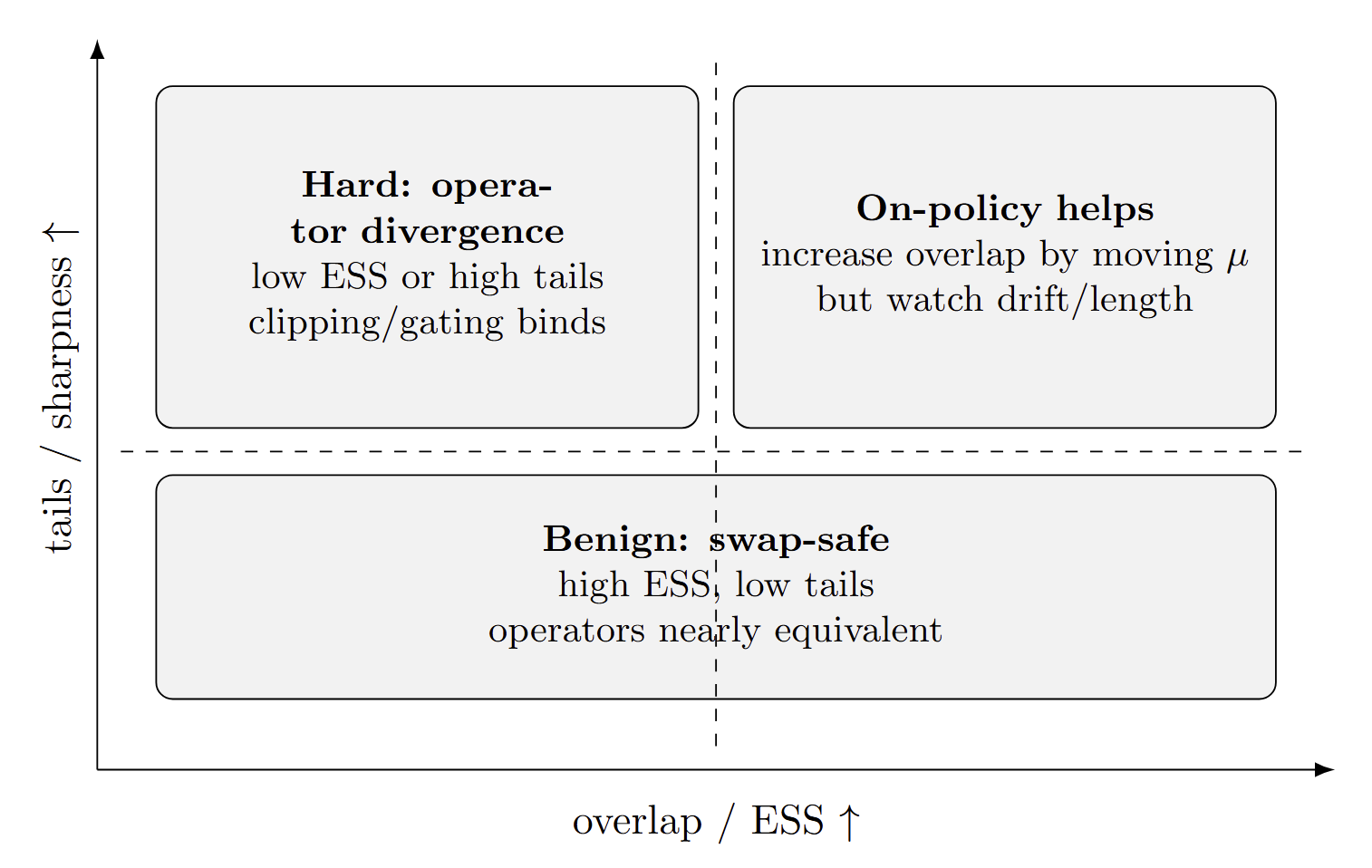

5. Regimes and operator swaps

Targets, operators and diagnostics give us a way to describe a single procedure. In practice we also care about how procedures relate to each other. A common operation is an operator swap: we keep the target design fixed (same utilities, anchors and sharpness, up to implementation details), but change \((\mu,\mathcal{A})\) . The TOD view suggests that such swaps should be analysed through the induced weights \(\tilde w\) and the resulting diagnostics, rather than by method names alone [8,7].

This section introduces a simple regime picture based on ESS and tail behaviour of \(\tilde w\) . It explains when different operators can be expected to behave similarly under matched budgets, and when differences in \(\mu\) and \(\mathcal{A}\) are expected to dominate.

5.1 Ratio landscape and regimes

For a fixed target \(q^*\) and operator proposal \(\mu\) , the importance weights

\[\small w_i \propto \frac{q^*(y_i \mid c)}{\mu(y_i \mid c)}\]on candidates \(y_i \sim \mu(\cdot \mid c)\) define the ratio landscape \(\tilde w\) on the sampled points. The context-wise ESS introduced in Section 3 is a compact summary of how concentrated these weights are.

Empirically, we see two qualitatively different regimes.

In the first regime, which we call swap-stable, ESS is consistently high relative to the candidate set size and the tails of \(\tilde w\) are moderate. For most contexts, several candidates carry non-negligible weight and trust-region mechanisms are rarely binding. In this regime, different operators that use the same candidates and utilities approximate similar target expectations. After matching compute and obvious hyperparameters, operator swaps tend to produce small changes in behaviour, and different methods behave like alternative implementations of the same design.

In the second regime, which we call operator-dominated, ESS is low for a substantial fraction of contexts or tail statistics indicate severe concentration. A small number of candidates carry most of the weight. Trust-region mechanisms such as clipping or gating are frequently active. In this regime, details of \(\mu\) and \(\mathcal{A}\) have a large effect on updates and selections. Operator swaps that leave the target unchanged can lead to systematic differences in behaviour, including instability, drift from anchors, or mode collapse, even under matched budgets [17,12,18,5,10].

The purpose of diagnostics is to distinguish between these regimes from quantities that can be logged in real systems. ESS and tail statistics are the primary indicators. Clip or gate activation rates and drift from anchors are secondary indicators that help interpret the operator’s response to the same ratio landscape.

5.2 Phase diagram

It is useful to think of these regimes in terms of a simple phase diagram. One convenient choice is to consider an axis measuring overlap or coverage, and an axis summarising tail severity.

On the horizontal axis we place a coverage indicator derived from ESS, for example the median or a low quantile of \(\mathrm{ESS}_{\mathrm{rel}}(c)\) over contexts. Low values indicate that the proposal \(\mu\) rarely proposes outputs that are representative under the target \(q^*\) ; high values indicate that \(\mu\) regularly visits regions where the target places mass.

On the vertical axis we place a tail indicator, such as the variance of log-weights or the typical maximum normalised weight within a context. Higher values correspond to heavier tails, in the sense that a few candidates dominate target expectations; lower values correspond to weight distributions that are closer to uniform on the sampled candidates.

In the lower-right region of this plane, overlap is good and tails are mild. This corresponds to the swap-stable regime described above. In the upper-left region, overlap is poor or tails are heavy. This corresponds to the operator-dominated regime. Between these extremes there is a transition region where behaviour depends on both coverage and operator design.

The exact choice of thresholds is application dependent, but the qualitative picture is robust: moving along the coverage axis and the tail axis changes how much freedom different operators have to behave similarly while targeting the same \(q^*\) . The phase diagram is a compact way to summarise this dependence.

5.3 Target–operator atlas

Targets and operators were introduced separately. In practice they are combined. It is therefore helpful to organise common recipes as points in a target–operator atlas.

Conceptually, we place target families from Section 2 along one axis and operator families from Section 4 along the other. Each cell of the resulting grid corresponds to a combination of target design and operator choice. For each occupied cell, we can record a few pieces of information: which concrete recipes it represents, what proposal \(\mu\) is used, what diagnostics are available, and which region of the phase diagram it typically occupies under realistic budgets.

For example, a cell combining a preference-induced target and an off-policy surrogate operator corresponds to DPO-style methods. A cell combining a two-anchor reward-tilted target and a proximal RL operator corresponds to PPO/GRPO-style RLHF. A cell combining the same target with a test-time search operator corresponds to best-of- \(K\) or reranking schemes that act only at inference. On-policy distillation populates cells where the target is teacher-driven and the operator is an on-policy projection based on student rollouts.

The atlas is not a new algorithm. It is a bookkeeping device that makes it explicit which targets and operators each named method is using, and which diagnostics are appropriate [7,8]. Once a method is located in this grid, questions about whether it can be “safely swapped” with another reduce to questions about their respective positions in the phase diagram: are they operating in a swap-stable regime relative to their shared target, or in an operator-dominated regime where diagnostics already indicate fragility?

In the next section we describe an adaptive controller that uses these diagnostics to adjust sharpness and anchoring during training, with the explicit goal of keeping the system in a swap-stable region when possible.

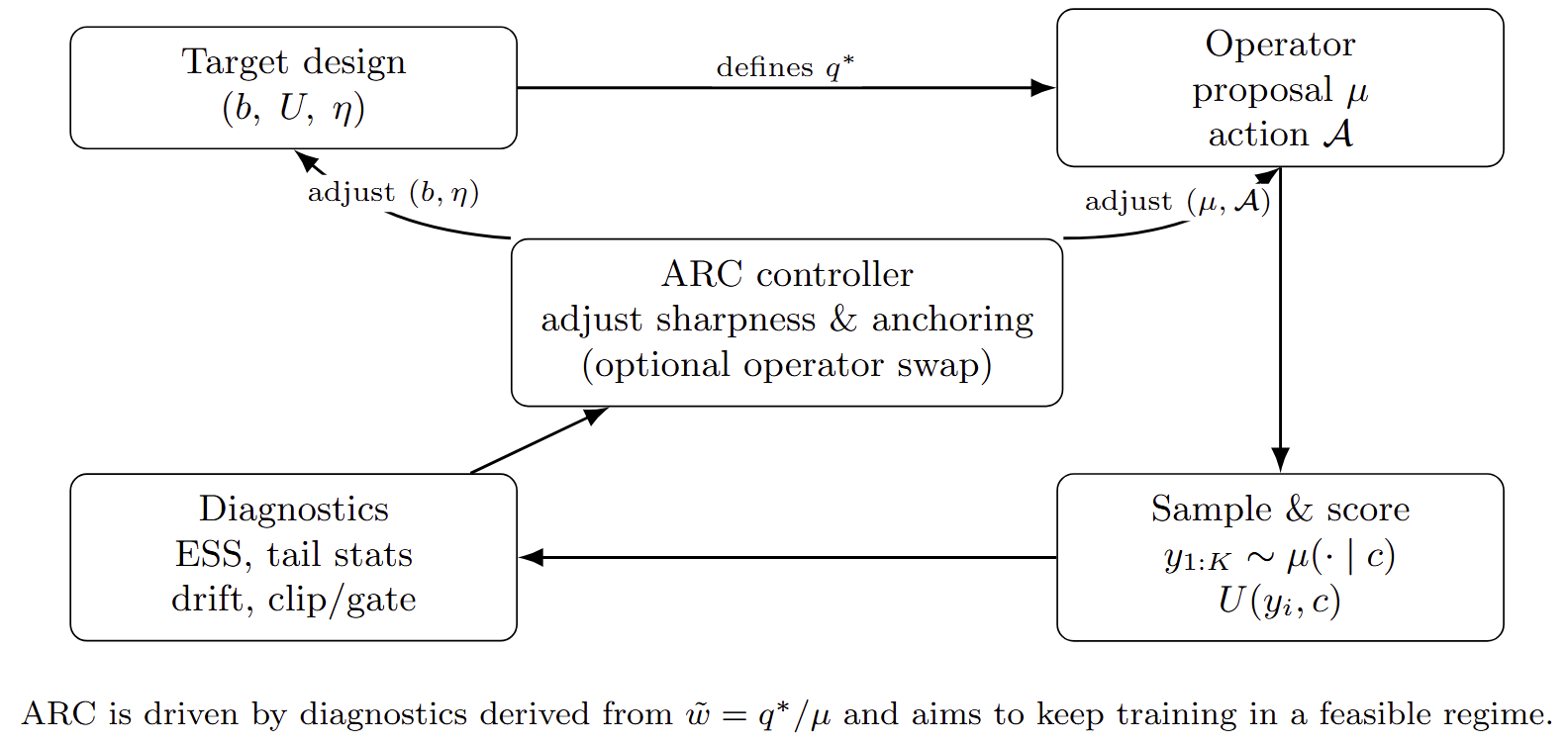

6. Adaptive Regime Controller (ARC)

The diagnostics in Sections 3–5 are descriptive: they tell us which regime a given configuration is in. In practice we also want to act on this information. The Adaptive Regime Controller (ARC) is a simple mechanism that adjusts target and operator hyperparameters during training, with the explicit goal of keeping the system in a regime where the target is feasible and operator swaps are stable.

ARC is not a new loss or model. It is a control layer that sits on top of existing targets and operators. At each training step it observes diagnostics computed from recent samples and adjusts a small number of knobs that govern target sharpness and anchoring, and, in some cases, selects between alternative operators.

6.1 Control variables and signals

In the utility-posterior targets of Section 2, the main design degrees of freedom are the sharpness parameters \(\eta\) and the coefficients that define the anchor \(b\) . For example, in the two-anchor RL design of Section 2.3, we have coefficients \(\tau,\beta\) in front of \(\mathrm{KL}(\pi\Vert\pi_{\mathrm{old}})\) and \(\mathrm{KL}(\pi\Vert\pi_{\mathrm{ref}})\) , which induce an effective base \(b_{\tau,\beta}\) and sharpness \(\eta = 1/(\tau+\beta)\) . In preference- or verifier-based targets, \(\eta\) directly controls how sharply we tilt toward higher scores.

ARC treats these quantities as control variables. At any given time it maintains current values for sharpness and anchoring, for example \(\eta_t\) and \((\tau_t,\beta_t)\) . It also has access to diagnostics such as aggregated ESS, tail statistics, drift from anchors, and clip or gate activation rates, computed over a recent window of training steps.

The high-level objective is to choose \(\eta_t\) and anchoring coefficients so that the induced ratio landscape \(\tilde w\) remains in a region where ESS is adequate and tails are not extreme, while still allowing the target to be sufficiently sharp to improve performance. When this is possible, ARC can also allow swaps from more expensive on-policy operators to cheaper surrogates without leaving the swap-stable regime.

6.2 One-step control logic

A single ARC step can be described informally as follows.

First, given the current policy and target parameters, we generate candidate outputs \(y_1,\dots,y_K\) under the operator’s proposal \(\mu_t(\cdot \mid c)\) and compute utilities \(U(y_i,c)\) and induced weights \(w_i\) . From these we derive ESS for each context and aggregate them into summary statistics such as the median or lower quantiles of \(\mathrm{ESS}_{\mathrm{rel}}(c)\) , together with tail indicators and drift metrics.

Second, ARC compares these diagnostics to pre-specified thresholds. If ESS is below a desired range or tail indicators are too high, it reduces effective sharpness. In a simple implementation this can be done by decreasing \(\eta_t\) or, in the two-anchor setting, increasing \(\tau_t+\beta_t\) while keeping their ratio fixed so that the geometric mixture \(b_{\tau,\beta}\) changes minimally. If drift from \(\pi_{\mathrm{ref}}\) is too large relative to a budget, ARC increases the weight on the reference anchor (for example, by increasing \(\beta_t\) while adjusting \(\tau_t\) accordingly), thereby pulling the effective base distribution closer to the reference.

Third, if diagnostics indicate that ESS is comfortably high and tails are mild over a sustained period, ARC may authorise a change of operator. For example, in a regime where on-policy RL updates and an off-policy surrogate both target the same design, ARC can switch from a more expensive on-policy operator to a cheaper surrogate or to an on-policy distillation step, while monitoring diagnostics to ensure that the swap does not push the system into an operator-dominated regime.

The concrete update rules for \(\eta_t\) , \(\tau_t,\beta_t\) , and operator choice can vary. The key property is that they are driven by diagnostics tied to \(\tilde w\) : ARC reacts when the ratio landscape becomes too sharp for the current proposal and budget, and relaxes constraints when the landscape is benign.

6.3 Interaction with operators

From the point of view of an operator family, ARC changes the effective target and, in some cases, the choice of operator itself. For example, in a proximal RL setting with two anchors, adjusting \((\tau_t,\beta_t)\) changes both the effective base \(b_{\tau,\beta}\) and the maximum step size implied by the trust region. In a preference-based or verifier-driven setting, adjusting \(\eta_t\) changes how much mass the target puts on the highest-scoring candidates relative to the proposal’s support.

Crucially, ARC does not modify the functional form of the operator. A PPO-style update remains a PPO-style update; an on-policy distillation step remains a projection toward a teacher; a test-time search routine remains a sample–score–select procedure. What changes is the region of the phase diagram in which these operators operate. By adjusting sharpness and anchoring in response to diagnostics, ARC attempts to keep the system in a region where ESS is sufficient, tails are moderate, and trust-region mechanisms are not constantly binding.

This perspective also clarifies the scope of ARC. It does not guarantee global optimality of any particular target. Instead, it provides a practical way to avoid obviously infeasible configurations—very sharp targets under weak proposals, or aggressive drift under tight reference constraints—and to make operator choices that are consistent with the current regime. In the experimental section we illustrate these points on controlled examples and on end-to-end post-training pipelines.

References

[1] Abbas Abdolmaleki, Jost Tobias Springenberg, Yuval Tassa, Rémi Munos, Nicolas Heess, and Martin Riedmiller. Maximum a posteriori policy optimisation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.06920, 2018.

[2] Rishabh Agarwal, Nino Vieillard, Yongchao Zhou, Piotr Stańczyk, Sabela Ramos, Matthieu Geist, and Olivier Bachem. On-policy distillation of language models: Learning from self-generated mistakes. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2024. arXiv:2306.13649.

[3] Kevin Lu and Thinking Machines Lab. On-policy distillation. Blog post, 2025. https://thinkingmachines.ai/blog/on-policy-distillation/. Accessed: 2025-12-18.

[4] Pier Giovanni Bissiri, Chris C. Holmes, and Stephen G. Walker. A general framework for updating belief distributions. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 78(5):1103–1130, 2016.

[5] Chang Gao, Chujie Zheng, Xiong-Hui Chen, Kai Dang, Shixuan Liu, Bowen Yu, An Yang, Shuai Bai, Jingren Zhou, and Junyang Lin. Soft adaptive policy optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2511.20347, 2025.

[6] Daya Guo, DeepSeek-AI, Dejian Yang, Haowei Zhang, Junxiao Song, et al. DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in LLMs via reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.12948, 2025.

[7] Hanyu Lai, Xiao Liu, Junjie Gao, Jiale Cheng, Zehan Qi, Yifan Xu, Shuntian Yao, Dan Zhang, Jinhua Du, Zhenyu Hou, Xin Lv, Minlie Huang, Yuxiao Dong, and Jie Tang. A survey of post-training scaling in large language models. In Proceedings of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL), 2025.

[8] Nathan Lambert. Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback. Online textbook, 2024.

[9] Sergey Levine. Reinforcement learning and control as probabilistic inference: Tutorial and review. arXiv preprint arXiv:1805.00909, 2018.

[10] Hanyi Mao, Quanjia Xiao, Lei Pang, and Haixiao Liu. Clip your sequences fairly: Enforcing length fairness for sequence-level RL. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.09177, 2025.

[11] Luca Martino, Víctor Elvira, and Francisco Louzada. Effective sample size for importance sampling based on discrepancy measures. arXiv preprint arXiv:1602.03572, 2016.

[12] Youssef Mroueh. Reinforcement learning with verifiable rewards: GRPO’s effective loss, dynamics, and success amplification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.06639, 2025.

[13] OpenAI. Reasoning models — OpenAI API. OpenAI platform documentation, 2025.

[14] Long Ouyang, Jeff Wu, Xu Jiang, Diogo Almeida, Carroll L. Wainwright, Pamela Mishkin, Chong Zhang, Sandhini Agarwal, Katarina Slama, Alex Ray, John Schulman, Jacob Hilton, et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2022. arXiv:2203.02155.

[15] Jan Peters, Katharina Mülling, and Yasemin Altun. Relative entropy policy search. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, volume 24, 2010.

[16] Rafael Rafailov, Archit Sharma, Eric Mitchell, Stefano Ermon, Christopher D. Manning, and Chelsea Finn. Direct preference optimization: Your language model is secretly a reward model. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2023. arXiv:2305.18290.

[17] John Schulman, Filip Wolski, Prafulla Dhariwal, Alec Radford, and Oleg Klimov. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.06347, 2017.

[18] Chujie Zheng, Shixuan Liu, Mingze Li, Xiong-Hui Chen, Bowen Yu, Chang Gao, Kai Dang, Yuqiong Liu, Rui Men, An Yang, Jingren Zhou, and Junyang Lin. Group sequence policy optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.18071, 2025.

Citation

If you find this work useful, please cite:

@misc{TOD2025,

title = {From Recipes to Regimes: A Target--Operator--Diagnostics Framework for LLM Post-Training},

author = {Wang, Shaobo and Fan, Junxin and Ren, Xingzhang and Liu, Dayiheng and Zhang, Linfeng},

url = {https://gszfwsb.github.io/blog/2025/TOD/}

year = {2025},

}